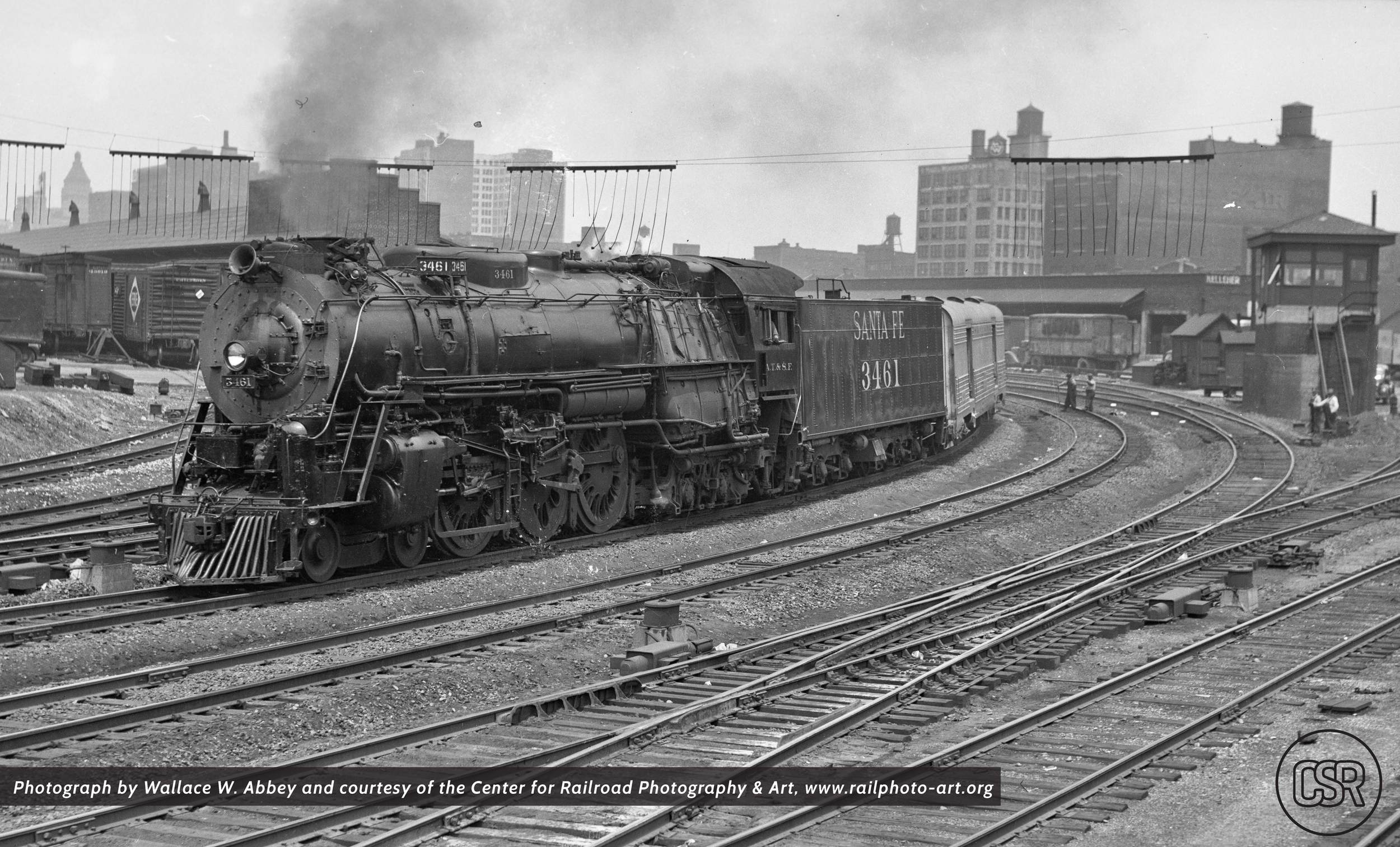

Locomotive 3463 was delivered to the ATSF by the Baldwin Locomotive Works on October 30, 1937, and it promptly went through a set of testing and trials. Initially all six 3460-class locomotive were assigned to the route between Chicago, Illinois, and La Junta, Colorado, hauling lightweight passenger trains such as the Chief. Given their prodigious power, however, management at the ATSF quickly reassigned the locomotives to heavier trains on the Chicago – La Junta run.

After its initial break-in period, locomotive 3463 was assigned to the Chicago-Kansas City passenger pool in November 1937. By the end of January 1938, locomotive 3463 and its fellow locomotives were assigned to the aforementioned Chicago-LaJunta pool, and was often responsible for hauling Trains 7-8, the Fast Mail Express. This assignment lasted through WWII until dieselization of Trains 7-8 in late 1946.

Locomotive 3463 remained assigned to service on the Illinois Division, though it was transferred to the Chicago – Newton, Kansas, passenger pool in 1947. Continual influx of additional diesel-electric locomotives through the late 1940’s resulted in engine 3463 being assigned to the Pecos Division, operating passenger trains between Albuquerque, New Mexico, and Newton, Kansas, in January of 1950. By April of that year, locomotive 3463 was transferred to the Eastern Division, which stretched from Oklahoma City to Kansas City via Newton. While on this division, locomotive 3463 handled trains such as the Oil Flyer (Kansas City – Oklahoma City) and The Scout, which operated between Kansas City and Belen, New Mexico (via Albuquerque, New Mexico).

The last regular passenger service locomotive 3463 was assigned to was ATSF Trains 27-28, the Antelope, which operated between Kansas City and Oklahoma City. This route was dieselized on March 18, 1953, causing 3463 to be bumped from regular passenger service.

The locomotive was then held at Newton, Kansas, for emergency protection. It hauled a variety of special assignments between March 1953, and December 1953, when it was last placed into the roundhouse at Emporia. The locomotive was kept in steam until March 25, 1954, at which point its fire was dropped. Records indicate locomotive 3463 was kept filled with warm water, in case it needed to be fired up, until November 15, 1954, when it was placed in Group 6 – Locomotives Held Out of Service.

Thanks to the detailed research of Larry Brasher, as outlined in his book Santa Fe Locomotive Development, we have a detailed account of the maintenance records of engine 3463 in its last decade of operation. He states:

Number 3463 had received her last Class 3 general overhaul at Albuquerque October 18, 1951, after making 378,909 miles since her previous Class 3. Cost of the overhaul was $27,248. She received a Class 5-H (heavy) overhaul at Albuquerque in November 1952 at 99,793 miles. She had accumulated a total of 122,493 miles since her last Class 3 when “laid up good” at Emporia on December 3, 1953. The total mileage of 3463 when she was retired was 1,850,476.

Brasher also provides exquisite detail as to the monthly mileage in operation of locomotive 3463 during that same timeline. It is interesting to note that, even toward the end of steam, the locomotive had a peak monthly mileage of 13,404 in May 1952, while assigned to operating the Oil Flyer between Kansas City and Tulsa, Oklahoma. Given that length of haul, that would mean the locomotive would have hauled approximately 56 one-way journeys between the two cities in one month, or approximately 28 days’ worth of round trips.

By November 1955, all remaining 3460-class locomotives had been designated as Form 531-A Special, Locomotives Held for Disposition, or for Sale or Scrap.

On February 9, 1956, a group of Topeka civic leaders and businessmen incorporated a not for profit corporation known as the Topeka Children and Santa Fe Railroad (TCSFR) to assist in acquisition of a locomotive from the ATSF and to place it in a park. By May 19 of that year, the ATSF ordered crews to paint locomotive 3463 and prepare it for donation to the City of Topeka.

As of June 30, 1956, locomotive 3463 had been repainted, the ATSF had stripped off all automatic train control equipment (most likely for use as spare equipment on a diesel-electric locomotive), and main rods had been placed onto the running board so that the engine could be towed from Emporia to Topeka.