Milwaukee County Zoo train locomotive No. 1924 hauls its train up the ~3% shop spur track burning 100% torrefied biomass. This image shows the exhaust at its approximate darkest during the testing in October.

Introduction

Entities working to provide biofuel to power plants are faced with the classic “chicken or egg” dilemma. Biofuel manufacturers need to have guaranteed orders for fuel from power plants to finance installation of fuel processing equipment, but power plants wont agree to order fuel until they can run tests, requiring hundreds of thousands of pounds of fuel that can only be made by the very equipment those manufacturers seek to install.

The Natural Resources Research Institute (NRRI), a collaborator with CSR, decided to go ahead and buy an “egg” to kick-start development - it purchased an industrial-scale biofuel reactor, in part thanks to CSR, and just recently completed commissioning and testing of the fuel.

We were fortunate at CSR to receive the very first load of torrefied biomass fuel from the NRRI reactor. After years of installation and preparation work, NRRI produced the first two 55 gallon barrels full of fuel for Zoo tests, 500 pounds in total. The path to get to those first 500 pounds was certainly a quest, but the results of the tests made the process entirely worth it!

This panorama shows the torrefaction reactor (center) as sited at NRRI's Coleraine Lab, a former Oliver Iron Mining Company locomotive shop.

Testing Round One

In early 2016, CSR began thinking of locations where it might be able to test torrefied biomass fuel in a steam locomotive boiler. At that time, NRRI was nearing completion of the installation of its reactor, and the belief was that fuel would be ready for testing by June.

Similar to the situation of making enough fuel for power plants, a standard gauge locomotive often requires between five and thirty-five tons of coal to operate. Making a batch of fuel that large for a set of tests would be both time consuming and expensive. Searching for a more manageable size, we decided that Milwaukee County Zoo, which operates a 15 inch gauge steam railroad with a locomotive of similar draft and boiler proportion to the those used in preservation around the U.S., would be an ideal test environment.

Our team reached out to Ken Ristow, whose job it is to maintain and operate the Zoo train. Ristow is no stranger to mainline steam, having been involved in the preservation of, and serving as the engineer on, such locomotives as Soo Line 1003 (1913 built 2-8-2), C&NW 1385 (1907 built 4-6-0) Soo Line 2719 (1923 built 4-6-2) and the Nickel Plate 765 (1944 built 2-8-4).

Ken Ristow is at the throttle of Soo Line 1003 as it races towards Hartford, Wisconsin, for its annual Christmas display in November 2015.

Ristow worked with Zoo management to approve CSR’s use of its equipment for testing. In short time, CSR was granted unencumbered access to the Zoo train equipment and its 1.2 mile-long railroad.

As the test date in June approached, word came down from NRRI that the torrefaction reactor they were installing was behind schedule. Never to disappoint, NRRI scrambled and located another torrefaction company to supply the required fuel for testing.

Given the short notice, the torrefied biomass fuel New Biomass Energy generously donated to CSR was delivered in traditional fuel pellet size as opposed to larger, coal-lump size as planned. CSR was able to work with the Zoo to modify the grates with stainless steel mesh and spacer pieces to permit air flow while preventing the small pellets from falling between the 3/4 inch pinholes of the grates on No. 1924.

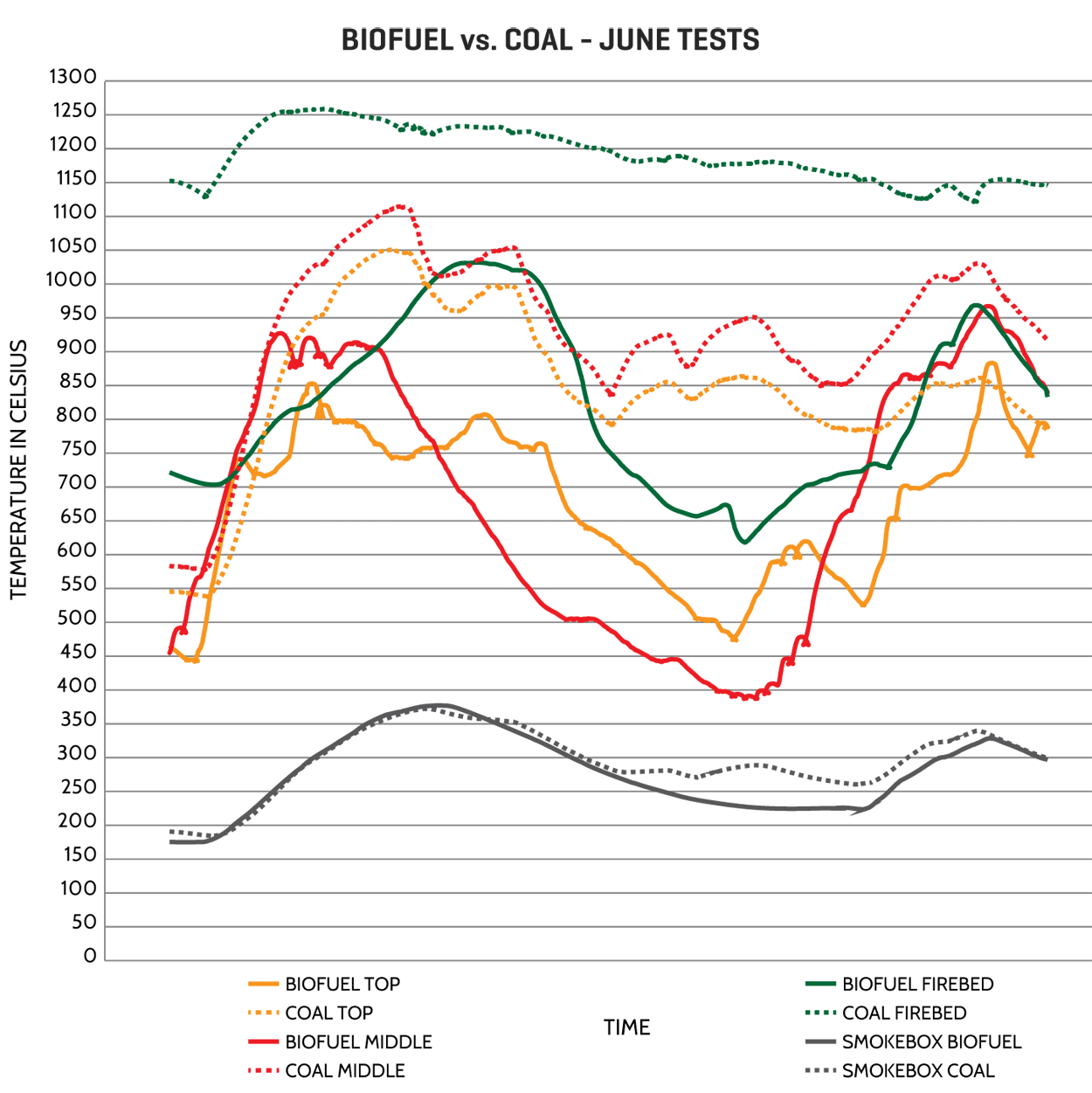

“We instrumented the locomotive with four, Inconel-sheathed thermocouples to gauge firebed, combustion space, and exhaust gas temperatures when burning coal vs biocoal,” explained CSR Senior Mechanical Engineer Wolf Fengler. “Tests were run on Saturday and Sunday, with trains Saturday burning coal and the first runs of Sunday burning biocoal.”

The modified grates and ends of the thermocouples can be seen in the accompanying photo. When testing, CSR burned both coal and biocoal on the modified grates as an experimental control.

“We used National Instruments hardware in concert with its LabView software to record second-by-second temperature data from the sensors,” said CSR President Davidson Ward. “Perhaps most exciting was the fact that three of the sensors were directly in the firebox, one submerged in the firebed and two at varying heights above, which provided insight into the combustion behaviors of each fuel.”

The initial results of the June tests indicated that the torrefied biomass had sufficient energy density and combustion characteristics to make steam, but we had concerns that the small pellet size was contributing to inefficient combustion. Since the small pieces packed together tightly and required many layers to build a sufficient firebed, we hypothesized that larger fuel pellets would generate equal heat with less smoke.

Keep in mind that, to build a firebed 3-3/4” deep with 3/8 inch diameter pellets requires at least ten fuel particles, whereas the same firebed depth with 1-1/4” particles requires just three pieces of fuel. With fewer pieces, there is a larger proportional area and simpler path for combustion air to flow between the fuel, thus aiding combustion.

Testing Round Two

Following the first set of tests, we circled back with NRRI to plan a second round.

As summer turned to fall, NRRI was making steady progress commissioning its large torrefaction reactor that, at full capacity, can produce 28,000 pounds of torrefied material per day. In early October, NRRI let us know it had more than 1,000 pounds of raw torrefied biomass on the ground ready to be densified and that they should be able to amalgamate it for a late October test.

Larger, "stoker coal-sized" torrefied biomass pellets. NRRI Photo

We reached back out to Ristow and his colleagues at the Zoo to see whether a test in late October would be possible. With little delay, we received approval for the second round of testing.

Graduate students and NRRI staff researcher Tim Hagen worked diligently to densify the test material, despite lacking ideal densification binder. Given the timelines, NRRI opted to proceed with the densification using material it had available to enable the next round of testing. The data that could be received from this round of testing would be quite helpful in informing future densification trials.

Loading barrels of fuel for shipment to Milwaukee. NRRI Photo

CSR President Davidson Ward drove to Coleraine, Minn., to pick up two barrels full of torrefied biomass pellets on the morning of Thursday, October 27. By that evening, he and the pellets were pulling into Milwaukee. To prevent large embers from leaving No. 1924, an engine that lacks both a firebox arch and a master mechanics’ front end, CSR’s Rob Mangels fabricated a spark arresting netting arrangement similar to that employed by the Colorado narrow gauge railroads.

We got to work that Friday, re-equipping the locomotive with thermocouple sensors and test-firing the engine on some of the torrefied biomass fuel. The pellets provided by NRRI were cylinders of approximately 1-1/4 x 2 inches, incidentally the same size as the stoker coal used by the Zoo to run its locomotives.

As shown at in the adjacent photo, the cylindrical pellets were relatively easy to crush, a result of the binder used in densification. By comparison, other pellets on hand densified with different binders were nearly impossible to crush, even with a hammer.

Upon the very first fireup, it became apparent that the torrefied biomass fuel burned much cleaner than coal , and that the larger biofuel pellets permitted a thicker firebed with little-to-no visible smoke as compared with the tests in June. Even when stoking the fire with many scoops of torrefied biomass at one time, the smokestack seldom showed more than a translucent gray haze.

On Saturday morning, we arrived early to fire up test locomotive No. 1924 on the torrefied biomass fuel. After about an hour of stoking, the boiler pressure gauge read just shy of 200 psi, and we were ready to begin operating trains.

With Ken Ristow at the throttle, the 4-6-2 gently pulled its train downgrade out of the shop and through the tunnel beneath Interstate Highway 94. With the entire train in the tunnel and at the base of an approximate 3% upgrade, Ristow hauled back on the throttle, agitating the torrefied fire unlike it had yet to experience.

The strong draft, combined with a dormant firebed, resulted in ash and cinders being blasted out of the stack. The engine roared upgrade with its 10 car test train in tow and, once the initial firebed cleaned, the stack went from hazy to clear.

Once at the top of the grade and onto the Zoo mainline, the train stopped to allow crew members to throw the switch. We then began three laps of continuous running to see how the fuel reacted in a “mainline” situation.

With 22” driving wheels and a loop of track approximately one and one-tenth of a mile in length, the tests were undertaken over a “scale” distance of 10 miles of railroad and a top scale speed of approximately 40 miles per hour. With the biofuel tests were completed, we switched the locomotive from torrefied biomass to coal and ran the balance of the normal trains using coal, logging comparative temperature data.

Results

The results of both biocoal/coal comparison tests, one in June with small pellets and one in October with large pellets, are shown below. It is interesting to note the difference in maximum temperatures between the tests, a function most likely of the difference in grates and the impact they had on the coal firebed. Both graphs represent data recorded on two runs and synced them up, shifting the data along the “x-axis” to relate to similar segments of the railroad. Click on the graphs to enlarge.

It is interesting to note that the torrefied biomass fuel is quicker to ignite than coal and, similarly, that it is quicker to fall off in temperature than coal. This is particularly evident when comparing the findings of the October tests, wherein fuel of analogous sizes were burned.

Given the differences in the energy content and bulk density of the fuels, these are logical results. Since the torrefied biomass pellets were of lower bulk density and of higher porosity, the increased surface area enables them to ignite quicker. The lower bulk density also means that the fuel reacts and burns quicker, resulting in a more rapid drop-off in temperature. That said, torrefied biomass burned with similar heat across the board, but the peak coal temperature was approximately 100 degrees hotter than the torrefied biomass.

Image from June showing combustion with thinner, small-pellet fire.

Image from October showing more even combustion from thicker, large-pellet fire.

The foregoing combined with the lack of ideal densification binder on the October tests resulted in the fuel tending to break apart prematurely when combusted, leading to fuel particles becoming entrained in the exhaust stream.

We will be working closely with researchers at NRRI over the winter to develop additional blends of densified torrefied biomass for use on the next series of fuel tests at the Zoo first thing in the Spring of 2017.

Next Steps - Transition to Standard Gauge

This stunning photo by Oren B. Helbok provides a great broad view of Everett Railroad No. 11. The railroad has offered CSR use of No. 11 for standard gauge fuel tests in 2017.

“The ability to test this alternative fuel is exciting for us; we all must find new and modern ways to help keep historic railroading alive for generations to come”

If the next round of tests at the Zoo continue to progress as the past ones, we will be ready to take the torrefied fuel research from the “test scale” at the Zoo to the “pilot scale.” This will be made possible in part through the generosity of the Hollidaysburg, Pennsylvania-based Everett Railroad (EVRR).

The EVRR operates a 1923-built 2-6-0 steam locomotive No. 11, hauling excursion trains through scenic rural Pennsylvania. The management and operations department is excited about the possibility of using torrefied fuel, and they approached CSR about the opportunity.

“We are facing a growing issue of finding a reliable source of high-quality coal that meets our specs and also is low smoke; large amounts of visible smoke is something that we must be very mindful of in the areas we operate,” said EVRR Steam Foreman Zach Hall. “The ability to test this alternative fuel is exciting for us; we all must find new and modern ways to help keep historic railroading alive for generations to come.”

According to Trains magazine, there are approximately 150 coal-fired steam locomotives in operation in the U.S. today, but changing economic and environmental conditions are making the procurement of coal ever more difficult.

EVRR fireman Stephen Lane shovels a scoop of coal into the firebox of No. 11 during a trip in December 2015. Photo by, and used courtesy of, Oren B. Helbok.

The U.S. has seen a huge decline in coal production, and it does not take much imagination to see a situation where the U.S. may also need to look at importing coal to fire steam locomotives, or even be forced to convert steam engines to oil and lose the art of hand firing.

Even in Great Britain, birthplace of the iron horse and bastion of steam preservation world-wide, news sources including the Telegraph and the BBC have been reporting such headlines as: “Coal crisis hits steam trains” and “Coal shortage hits Vintage Trains and Severn Valley Railway.”

Thanks to the generosity of EVRR President Alan Maples, the railroad has offered to allow CSR to test fuel on No. 11 over three days in the coming operating season, an in-kind contribution of $9,000 towards this fuel research.

CSR seeks to raise an additional $27,000 to cover the costs of fuel densification studies this winter, an additional round of tests at the Milwaukee County Zoo in the Spring, as well as fund the manufacture of approximately 10 tons of torrefied fuel for use by the EVRR on tests with No. 11.

Can we count on your support as we work to keep steam alive?

We strive to keep this history alive, and our Team is confident that, with the support of many, CSR can help ensure a bright future for steam in generations to come.

Already, this important fuel research has been supported by the outstanding assistance of the Milwaukee County Zoo, the Natural Resources Research Institute, New Biomass Energy, the American Boiler Manufacturers Association, and the support of CSR’s donors, including generous contributions by Bon French and Fred Gullette. Additional research into the conversion of used railroad ties into torrefied biomass was also underwritten through generous contributions of the Indiana Rail Road. Will you help make this research a reality?

More details on densification research, additional small scale tests, and the planned full scale test will be made known in the coming months!